In 1666, London blazed for days. A long dry summer, densely packed homes, and flammable building materials were a recipe for disaster. A stray spark at a bakery on Pudding Lane became an inferno, and destroyed much of London. This would become known as the Great Fire of London.

It was a huge financial blow to the city: the cost of the fire was estimated to be £10 million at a time when London's annual income was only £12,000. Many people were financially ruined and debtors' prisons became over-crowded.

The enormous losses suffered after the Great Fire of London led to the establishment of fire insurance, where people paid a fee to an insurance company to insure their property against damage. The first insurance company, called the Fire Office was formed in 1680 by the economist and financial speculator Nicolas Barbon. By 1705 it had changed its name to the Phoenix after the Greek mythological bird that rose from the ashes.

To protect the properties of their customers and to reduce their own losses most London insurance companies employed up to 30 Thames watermen to put out fires. However, the term ‘fire brigade’ was not used until the early 19th century.

Metal plaques with the brightly painted emblems of each fire insurance company were placed high up on the buildings of insured properties. As the plaques were made of metal, they were more likely to survive any fire. Their main purpose was to prove that the property was insured in the event of a claim. The height of the plaques prevented people from stealing them and fixing them to their own properties. They also served as advertisements and in the days before street numbering, as direction finders.

Popular stories suggest that insurance firemen would leave a building to burn if it wasn’t insured or insured with a rival company. There is little real evidence to suggest that this was the case. In fact, evidence shows that insurance companies had strict rules that on pain of dismissal, their firefighting teams should attend every fire they encountered, whether the property was insured or not and regardless of which company it might have been insured with. Any fire left unchecked could spread to whole streets or neighbourhoods and involve the insurance companies in large scale losses. Mutual co-operation was therefore extremely important.

Right: Example of a Sun Insurance Company fire mark

You can still see some old fire marks on buildings today – don't forget to look up as you walk around older parts of London.

Each company adopted elaborate and brightly coloured uniforms. This was partly for identification purposes but mostly as a means of publicity. New uniforms were provided each year to coincide with the insurance company's annual meeting day and this was an opportunity to parade their men through the streets in a public procession accompanied by a band of musicians. The custom was later expanded so that firemen gradually took part in many other public processions and became an important part of London civic life.

Firefighting equipment remained very basic but included buckets, axes and preventers which were similar to boat hooks between 8 to 15 feet long. The preventers were used for tasks such as pulling down burning embers. These are sometimes referred to as fire hooks.

Right: Print of a firefighter from the Hope Fire and Life Assurance Company, in around the early 1800s

Fire engines were used by the insurance brigades from the early 1700s although not in great numbers. The most successful fire engine manufacturer of the 18th century was Richard Newsham who took out a patent in 1721 for a 'new water engine for the quenching and extinguishing of fires'. This was claimed as the first to provide a continuous jet of water. Newsham had many rivals however and an earlier patent for the same idea had been issued in 1712 to John Gray and Nicholas Mandell.

Maintaining a constant water pressure during large fires involved continuous pumping. This was exhausting physical work which called for a relay of pumpers, many of them volunteers. Providing some form of refreshment was essential. As water supplies at that time were not safe for drinking, the pumpers, were provided with beer paid for by the insurance companies. In practice the Brigade Foreman would claim expenses for the amount of beer which was supplied.

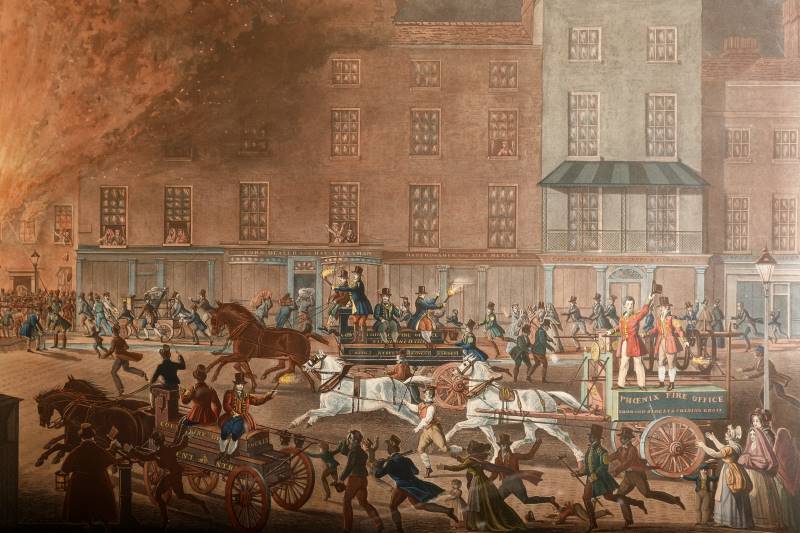

Left: Print titled “London Fire Engines, the noble protectors of life and property”, published 1832

Ladders were not part of the equipment carried by the insurance brigades as their priority was saving insured property rather than people. A Fire Escape Society was therefore formed in 1828 to provide manned, wheeled escape ladders.

These were placed in certain streets each night so that in the event of a fire they could be pushed to the relevant house and used to rescue anyone who was trapped. The ladders were often kept in churchyards during the day and therefore rescues only took place during the night-time. The Society was replaced in 1836 by the Royal Society for the Protection of Life from Fire (RSPLF) which shared the same aims.

In the 1900s, some fire escape ladders had a canvas chute so that ladies could slide down without showing their ankles.

Growing trade during the industrial revolution had created many more fire hazards and an increased demand for fire insurance. One particular hazard was the densely packed waterside areas with high numbers of moored ships and a growing volume of flammable goods stored on the quays in large warehouses which continued to expand in size. This was the type of warehouse which later featured in the great fire of Tooley Street in 1861.

This in turn gave rise to a growth in the number of insurance companies and to the level of competition between them. There was therefore the need to reduce the cost of so many competing fire brigades and to increase efficiency by combining their resources. From the 1st January 1833, ten independent insurance brigades merged to form the London Fire Engine Establishment (LFEE) and others gradually joined them in the next few years.

The first Superintendent of the London Fire Engine Establishment was James Braidwood, previously the Firemaster of Edinburgh Fire Brigade. He had already built an excellent reputation for his training methods and successful leadership. Known as the ‘Father of the British Fire Service’ he introduced many firefighting principles that remain in use today. These include an emphasis on training and a scientific approach to tackling blazes. He also introduced more practical uniforms with some measure of personal protection.

The London Fire Engine Establishment became the Metropolitan Fire Brigade in 1862, following the tragic events of the Tooley Street fire, and this paved the way for the modern London Fire Brigade.