London in 1666

Back in the 1660s, people were not as aware of the dangers of fire as they are today. Buildings were made of timber – covered in a flammable substance called pitch, roofed with thatch – and tightly packed together with little regard for planning. About 350,000 people lived in London just before the Great Fire, it was one of the largest cities in Europe.

Homes arched out over the street below, almost touching in places, and the city was buzzing with people. Lots of animals lived London too – there were no cars, buses or lorries back then – so as well as houses, the city was full of sheds and yards packed high with flammable hay and straw.

Following a long, dry summer the city was suffering a drought. Water was scarce and the wooden houses had dried out, making them easier to burn... it was a recipe for disaster.

Did you know?

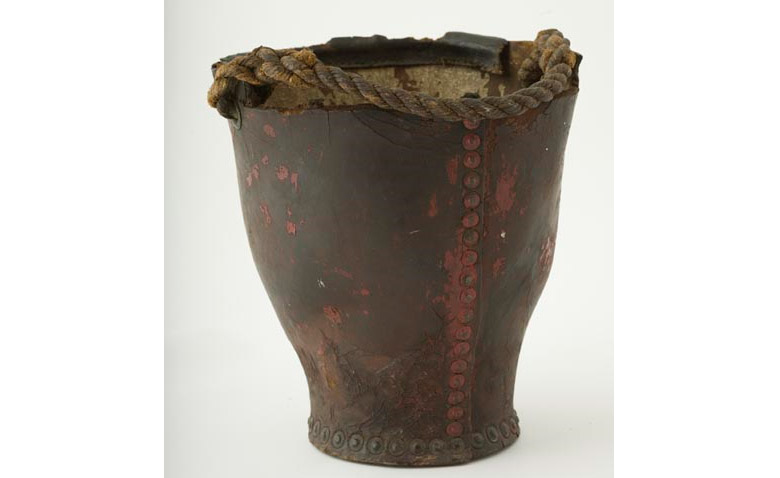

In 1666 there was no organised fire brigade. Firefighting was very basic with little skill or knowledge involved. Leather buckets, axes and water squirts were used to fight the fire – but had little effect.

Jane Rugg, Museum Curator

The fire that changed our city forever...

The Great Fire of London started on Sunday, 2 September 1666 in a baker's shop on Pudding Lane belonging to Thomas Farynor (Farriner). Although he claimed to have extinguished the fire, three hours later at 1am, his house was a blazing inferno.

At first, few were concerned – fires were such a common occurrence at the time. However, the fire moved quickly down Pudding Lane and carried on down Fish Hill and towards the River Thames. It spread rapidly, helped by a strong wind from the east. When it reached the Thames it hit warehouses stocked with combustible products including as oil and tallow.

Fortunately, the fire didn't spread south of the river – but only because a major blaze in 1633 had already destroyed a section of London Bridge.

Samuel Pepys observed first hand...

Samuel Pepys, a man who lived at the time, kept a diary that has been well preserved – you can read it in full here. He was a Clerk to the Royal Navy who observed the fire. He recommended to the King that buildings were pulled down – many thought it was the only way to stop the fire.

The Mayor was ordered to use fire hooks to pull-down burning buildings but the fire continued to spread. People forced to evacuate their homes chose to bury or hide what valuables they couldn't carry. Pepys himself buried his expensive cheese and wine, and carted his other belongings off to Bethnal Green.

From the diary of Samuel Pepys, Monday 3 September 1666:

About four o’clock in the morning, my Lady Batten sent me a cart to carry away all my money, and plate, and best things, to Sir W. Rider’s at Bednall-greene. Which I did riding myself in my night-gowne in the cart; and, Lord! to see how the streets and the highways are crowded with people running and riding, and getting of carts at any rate to fetch away things.

So how did they put out the Great Fire of London?

Pepys spoke to the Admiral of the Navy and agreed they should blow up houses in the path of the fire. The hope was that by doing this they would create a space to stop the fire spreading from house to house.

The Navy – which had been using gunpowder at the time – carried out the request and the fire was mostly under control by Wednesday, 5 September 1666. However small fires continued to break out and the ground remained too hot to walk on for several days afterwards.

Pepys recorded in his diary that even the King, Charles II, was seen helping to put out the fire.

From the diary of Samuel Pepys, Wednesday 5 September 1666:

Lord! what sad sight it was by moone- light to see, the whole City almost on fire, that you might see it plain at Woolwich, as if you were by it.

What happened after the fire?

London had to be almost totally reconstructed. Temporary buildings were erected that were ill-equipped, disease spread easily, and many people died from this and the harsh winter that followed the fire.

As well as loss of life, the financial costs were staggering. 13,200 houses, 87 parish churches, The Royal Exchange, Guildhall and St. Paul’s Cathedral – built during the Middle Ages – was totally destroyed. The costs were estimated at £10 million.

Shortly after, clever businessmen spotted an opportunity to provide the surety of insurance, though reduced their risk of financial losses by employing men to extinguish fires: the first fire brigades were formed. The story continues on the early fire brigades page – find out about these brigades, how they worked, and where beer tokens came from.

A fresh start for London

Sir Christopher Wren planned the new city and the rebuilding of London took over 30 years. The site where the fire first started is now marked by a 202-foot monument built between 1671 and 1677.

Bitesize learning

This activity is a fascinating short video based around the Great Fire of London, which is in line with the National Curriculum for KS1 pupils (ages 5-7).

If you want to continue the learning after watching the video you can also download the activity sheets so your child can design their very own firemark, and try some other fun activities.

Join our museum mailing list

Although our museum is closed to the public, while we are planning to develop a new museum, you can join our digital newsletter.

We'll keep you updates about what we are doing virtually, and in person, and there are lots of fascinating insights into the long history of London Fire Brigade.

Join the mailing list