For Black History Month historian Stephen Bourne tells us about some of the Black people involved in the fire service in the 1930s and 40s. By this time there were established Black communities in several major cities including Liverpool and Bristol, as well as London. The growth of the British Empire at the end of the 19th century lead to increasing numbers of Black people coming to Britain from both Africa and the Caribbean, often to study, or to find employment. We don’t yet know how many Black people were involved in London Fire Brigade in this period, partly because they can be difficult to identify in our records, but as Stephen shows, through contemporary accounts and individual stories there are many insights into Black people’s contribution to the Home Front.

Fernando Henriques (top row, with the beard) with fellow members of the Auxiliary Fire Service (not yet identified) in Hampstead, London.

Article by Stephen Bourne

Founded by a Jamaican-born South London doctor, Harold Moody in 1931, The League of Coloured Peoples quickly established itself as Britain’s most influential Black action group. Its wartime newsletters are an invaluable source of information about Black Britons in wartime, including civilian defence workers. After the London Blitz started in September 1940, the League began to publish reports about the contributions made by Black citizens. For instance, in December 1940, A. A. Thompson, the Jamaican academic and general secretary of the League, praised the work of Black ‘front liners’. He said:

‘In London especially one is amazed at the number of coloured men who have accommodated themselves to the novel circumstances of the war, and are to be found working as Wardens, A.F.S. (Auxiliary Fire Service) men, members of Stretcher Parties, First Aid units, and Mobile Canteens. One feels that the contribution these men are making to the defence of London ought to be given the fullest publicity.’

Esther Bruce (1912-1994) and Laureen Goodare (1911-1983)

From left to right: Dora Plaskitt, Kathy Joyce (Stephen Bourne’s mother) and Esther Bruce in 1942. Credit Stephen Bourne.

Regrettably, A. A. Thompson failed to acknowledge that Black women also took part as ‘front liners’. I was made aware of this at an early age through my relationship with Esther Bruce, my adopted aunt. She was a Black Londoner, born in 1912, who came into my family during the London Blitz following the death of her Guyanese father. My great grandmother ‘adopted’ her and when I was a teenager we formed a close bond and she shared with me many stories about her eventful life, including the war years. In 1941, Esther gave up her job as a seamstress to do war work. She said: “I worked in hospitals as a ward cleaner, down on my hands and knees with a buffer and polish. I worked in two hospitals, Fulham, where Charing Cross Hospital is today, and Brompton.”

In addition to cleaning hospital wards, Esther volunteered as a fire guard or fire watcher. This position was created as a result of the night of 29/30 December 1940, when the City of London was devastated by incendiary bombs, 18 inches long and weighing only a couple of pounds, but filled with highly combustible chemicals and dropped in clusters to spread fires. These also created targets for the night-time German planes which followed and carried high explosive bombs.

Example, from the collection, of a stirrup pump and bucket, used during the Second World War. The pump was operated by two or three people; one directed the water from the nozzle and the second person pumped the water from the bucket, standing on the circular metal 'stirrup' to keep it stable. A third person could refill the bucket and takeover from the other two when needed.

Armed with a stirrup pump, a helmet and an armband labelled ‘Fire Guard’, Esther stood on the roofs of Fulham and Brompton hospitals during air-raids, helping to put out any fires caused by incendiaries. It was a hazardous job, and many women who had not enlisted in the armed forces volunteered. She said:

“It was dangerous and I was scared but, when the air-raids continued, we knew we would all have to do our bit and pitch in.”

At the end of the war, Esther took my mother, Kathy, aged 14, to see St Paul’s Cathedral. Like so many others, Esther found it hard to believe that St Paul’s had survived the German bombardment of London. For many, including Esther, the beautiful and majestic cathedral symbolised the hope and strength of the British people. “Look at St. Paul’s Cathedral”, Esther said to Kathy. “There’s not a mark on it. We’re lucky. We’ve still got half a street, but some poor souls have ended up with nothing.” In 2022, a Hammersmith and Fulham Blue Plaque bearing Esther’s name and acknowledging her war service was unveiled outside Charing Cross Hospital.

Esther Bruce’s Hammersmith and Fulham Blue Plaque outside Charing Cross Hospital. Credit Stephen Bourne.

My friend Cleo Sylvestre has kindly shared with me the story of her mother Laureen Goodare, born mixed race in Hull in 1911. Before the war, Laureen worked as a cigarette seller and cabaret dancer in one of London’s most popular Soho nightclubs, the Shim Sham Club. During the war, Laureen worked at the Manchester Square Fire Station in Marylebone. Cleo recalled: “I seem to remember she said she was in the incident room recording fires, fallen bombs, etc. Whilst there she made two very good lifelong friends, the underwater archaeologist Honor Frost and the poet Daria Hambourg, the daughter of the renowned pianist Mark Hambourg.” Laureen didn’t elaborate about her time in the Fire Service but, says Cleo:

“I do remember her telling me that, one night, when she was on her way home, there was an air raid warning. She found an air raid shelter and was surprised to find that it was empty. In the morning, after the raid was over, she realised why. It had no roof!”

Fernando Henriques (1916-1976)

Fernando Henriques (top row, with the beard) with fellow members of the Auxiliary Fire Service (not yet identified) in Hampstead, London.

When the Second World War began on 3 September 1939, Fernando Henriques applied to join the Royal Air Force, but they didn’t want him, or any man of colour. It took a year for the RAF to end this appalling discrimination or ‘colour bar’ as it was known back then. This was partly due to the campaigning work of The League of Coloured Peoples led by Dr Harold Moody, which advocated for the needs of Britain’s Black community.

Fernando Henriques had been born into a middle-class Jamaican family. They left the island in 1919, when Fernando was three years old. The Henriques family made a new home for themselves in St John’s Wood in north London. Fernando was educated at a Catholic grammar school and the London School of Economics. However, by the time the RAF lifted its ‘colour bar’, Fernando had found an alternative wartime occupation. He joined the Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS) in 1939 and remained a fireman for three years. He later recalled:

‘Told on the outbreak of war that I was not white enough to fly, I was permitted to defend London in another capacity. With a friend from schooldays – inevitably white – I joined the Auxiliary Fire Service. We were accepted with enthusiasm, for in those days it was thought London would be inundated with fire bombs almost immediately. Issued with uniforms, we were swiftly assigned to one of the improvised fire stations which had mushroomed all over the city on the outbreak of war.’

The ‘improvised fire station’ referred to by Fernando was a requisitioned middle-class girls’ school in Maresfield Gardens in Hampstead. At the Maresfield Gardens AFS, Fernando befriended the poet Stephen Spender, novelist William Sansom and the painter Leonard Rosomon, who began making paintings of his experiences as a firefighter during the Blitz. Fernando described the fire service in London in those days as a kind of refuge for intellectuals. He said:

‘All classes were represented in these services and, because of the atmosphere induced by the common crisis of war, fire stations and the like became a kind of utopian democracy. In my own case, located in an inner suburb of London’s Hampstead – which has always had a reputation for liberalism and creativity – firemen were everything from greengrocers to poets…The working-class element in the station respected the intellectual group which by a process of osmosis both educated, and were educated.’

Cannon Street, oil, painted by Paul Dessau. The view of St Pauls from Cannon Street, with buildings all around it consumed by fire.

As a firefighter during air-raids, Fernando found himself constantly on the alert but, he said, “the Fire Service provided long periods of standing-by when I could study. This I did, and to the surprise of both my friends and myself obtained an Open Scholarship to Oxford.”

George A. Roberts (1891-1970)

George, on the far left, alongside fellow AFS personnel. Courtesy of the Roberts Family.

In 1939, George A. Roberts was living in Warner Road, Camberwell in south east London. George was a Trinidadian who had served in the First World War in the Middlesex Regiment. It is likely that George’s First World War experiences on the battlefields of Loos, the Somme and in the Dardanelles, prepared him for the onslaught of the London Blitz. When the Second World War began, George was too old for combat so he trained with the Auxiliary Fire Service, which was known as the National Fire Service (NFS) from 1941. His base was New Cross Fire Station and in 1943 he was made a section leader. As a brave fire fighter, he faced constant danger throughout the Blitz. He put out fires and saved lives while the bombs fell and exploded.

George A. Roberts photographed by John Hinde supervising the Discussion and Education Group at New Cross Fire Station. Source: Stephen Spender, Citizens in War – And After (1945). Credit Stephen Bourne.

In addition to his fire service duties, George was responsible for organising the Discussion and Education Groups of the wartime NFS. He realised that fire officers had time on their hands between air-raids and the discussion groups helped them to relieve the boredom and tension. As such, George met and befriended a number of prominent artists and writers including Norman Hepple, who painted his portrait. In 1943 Hepple’s portrait was included in a pamphlet entitled Jim Braidy – The Story of Britain’s Firemen and is now in a private collection.

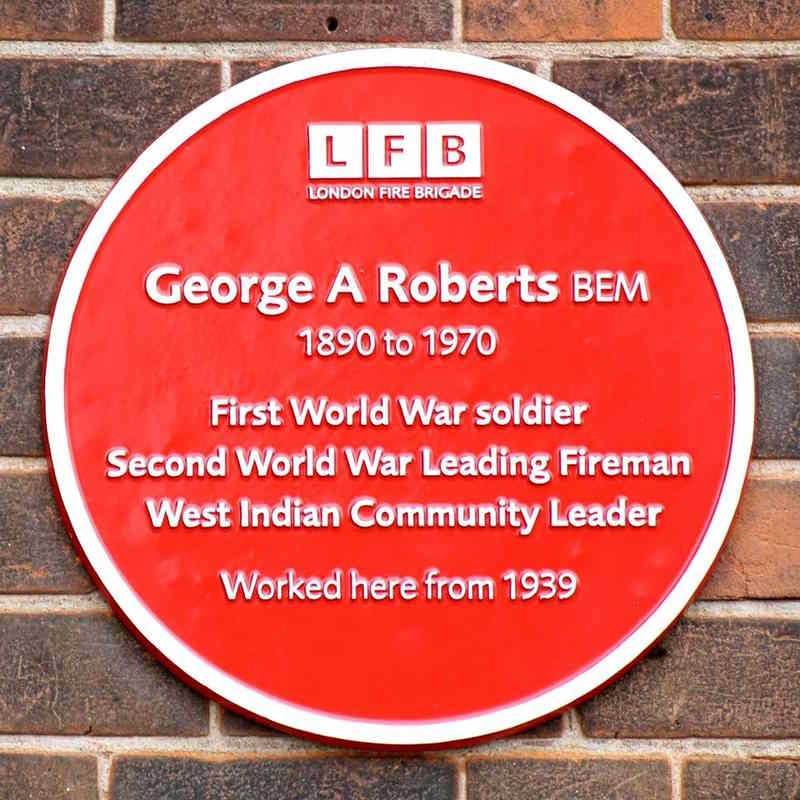

George A. Roberts’s London Fire Brigade Red Plaque unveiled at New Cross Fire Station in 2018.

In 1944 George was awarded the British Empire Medal which was presented to him by George VI at Buckingham Palace. In 2018 London Fire Brigade invited George’s great-granddaughter Samantha Harding to unveil a Red Plaque in his honour at New Cross Fire Station.

See also The Life and Legacy of George Arthur Roberts, which is maintained by the Roberts family, and our LFB ‘Trailblazers’ profile.

Stephen Bourne has been researching and writing about Black history for over 30 years and was a founder member of the Black and Asian Studies Association. He is the author of Under Fire: Black Britain in Wartime 1939-45. Information about Stephen’s other books can be found on his website.